Zhang Wen Hai in Brussels, capital of Europe.

“In Europe I learned the beauty of the Unfinished“

Originally from northern China, but born in Shanghai because his parents worked there, the painter Zhang Wenhai spent as much time in China as in Belgium, which is to say if he knows the artistic questions that animate the two countries. His singular approach borrows from these two cultures their own beauty. This fine technician trained in engraving with us is also a thinker of his art dedicated to a practice of the borders between “abstract and figurative”, two Western concepts that the Chinese understand in their own way, a way that may well positively upset our European categories !

LHCH had the chance to visit the new studio-gallery of the Chinese artist in Brussels. Full interview here.

LHCH: What was your training in China, first of all?

ZHANG WENHAI: I had already started this apprenticeship in artistic secondary school. The lessons were half in practical work. There I learned Western-style academic techniques such as classical drawing, still lifes, watercolour, oil painting and sculpture.

LHCH: Training completed in Europe.

ZHANG: The paradox is that when you arrive in Europe, you are asked to forget all the technique learned in China and “let your imagination run wild”. It is very difficult to live at the beginning. You have to adapt. The teacher is only there to provide a “thought solution”, a creative angle. And this, from the first years of candidacy! So, I was surrounded by students lacking technique and solid artistic bases who already wanted to start creating their work! In China, it is the reverse order. I arrived with the ability to draw shapes, bodies in an artistic and rigorous way. Here, I feel like the students thought I was coming out of a “cage”, that I was over-educated. Painful experience.

LHCH: But to learn Chinese art as such, how does it work? At what level of study?

Zhang: After high school. At university or academy. Personally, I did 2 out of 4 years at the Shanghai Academy then I came to Belgium at the invitation of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. But in China, before having professional status, I was a teacher of calligraphy and Chinese painting for children.

LHCH: In what year did you arrive in Belgium? Was it easy to get a visa?

ZHANG: Very early 1999. No. It was necessary to manage equivalences and communication between the two academies. In addition, I needed someone to support me financially here. I was 19 years old. Without a Luxembourg friend of my father, nothing would have been possible. Finally, I was asked to do a year of French before starting artistic classes.

LHCH: You were talking about a China still a bit locked in academicism, but in the 90s, during your adolescence, there was already the wave of giant artists like Yue Minjun who revolutionized contemporary art even at the global level. ! And there was very soon the 798 artistic industrial zone in Beijing.

ZHANG: There was no internet back then. This novelty had not really circulated in our huge country at that time. And moreover, the concept of contemporary art is primarily Western. You started early. You quote Yue Minjun, but it was still figurative, or rather “cynical realism”. Has China already really entered its own revolutionary phase of contemporary art? What would truly Chinese contemporary art be? In the 1980s and 1990s reference was made to Mao’s Little Red Book or the Cultural Revolution. But isn’t this a game of comparison with Europe? A western system only filled with Chinese folk notes…

LHCH: These artists did not, however, make the leap to go to Europe. They stayed in Beijing.

ZHANG: Exactly. Apart from Ai Wei Wei or especially Zao Fou Ki, who really came to settle in France, our artists know Europe rather poorly. They copied a structure and filled it with their culture. But without deep reflection. Here I learned to understand why you often reject technique for freedom and abstraction.

LHCH: And why do you think?

ZHANG: Multiple revolutions since the beginning of the 20th century. But in my opinion this way of rejecting the representation is exaggerated.

LHCH: For example?

ZHANG: We have another relationship with the outside world. In China, we have to know how to express things that we have experienced… Here, the young students are only thinking. But after brilliant experiments at the academy, when they graduate, what is left? What will they do concretely in their work as artists if they only have concepts in mind? How to materialize these ideas? No, really their true freedom would be to have access to artistic techniques. To be free is to lead oneself where one wants to go. Self-discipline. You must first know the means of expression in order only then to select them and forget others.

LHCH: Are you talking about the maturation of an artist?

ZHANG: Yes, I call it “fermentation”. There are things that lie within us and develop. Others disappear over time. But you need a raw material for that.

SUBLIMATED ENGRAVING AND MAROUFLAGE

LHCH: Or digestion? And more specifically, what did you learn here? I had seen your study work in 2008.

ZHANG: There are compulsory courses in mixed techniques depending on the term. I particularly like the metal worked with a chisel, in the Italian manner of the 13th century before the techniques of etching. It takes a year to learn how to draw a straight line. And another year to draw a curved line! On the banknotes the drawings were made in this way. Today, no one uses a chisel except in jewelry stores. I like the result of this type of engraving. Fine and regular.

LHCH: And you continued?

ZHANG: No, not really. But it taught me a lot of things. In license, I also learned the technique of marouflage (from China) that I appropriated. The idea is to protect fragile paper such as calligraphy. I had the idea of combining engraving with masking. You can print several sheets, transparent, with the engraving. So these sheets with contemporary abstract etched patterns, I smooth them on Chinese paper, often on rolls. We can clearly see the two types of superimposed papers. This is my first technique for which I received an award abroad!

LHCH: When I see your current more abstract work, I think that like other Chinese artists your vision is still quite figurative.

ZHANG: Is a task real? And if we enlarge it a lot? Doesn’t it become abstract? And a close-up knot in a tree? Exciting questions.

LHCH: How did you go from this 2009 technique to today’s charts?

ZHANG: There is a continuity because the colors of my paintings do not come from me but from the papers precisely. So there is still this idea of paper and texture. Today I layer the textures. But I change the glues. With plant or animal origins. Then I can mix the ink with the glue and create more authentic textures.

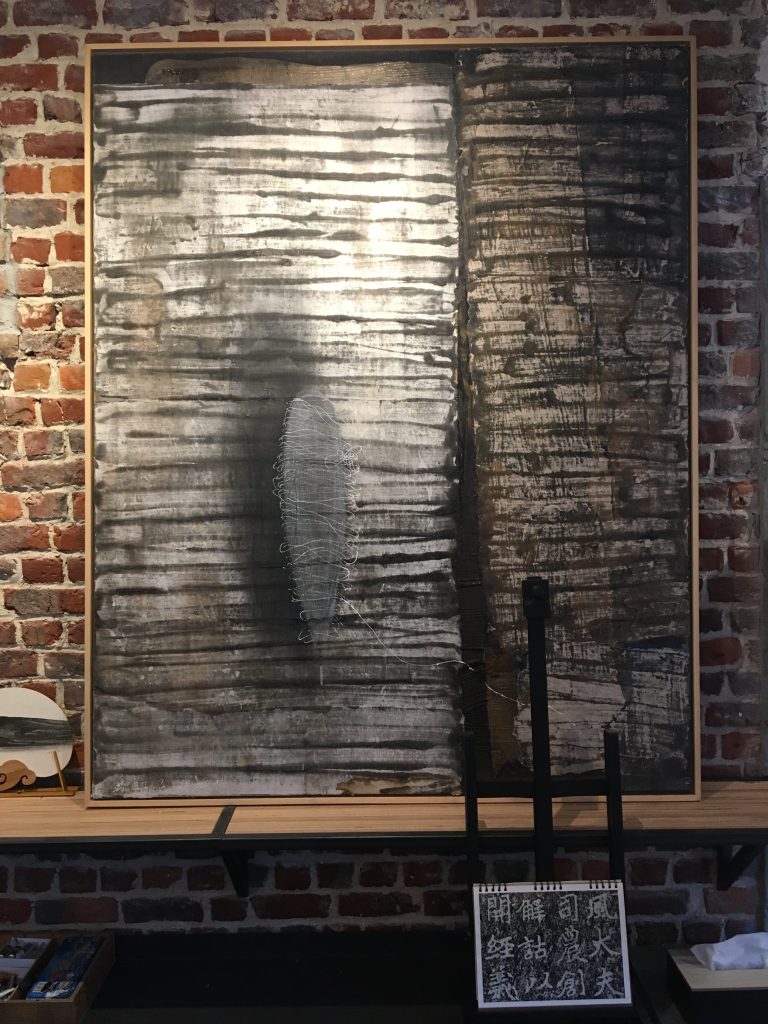

LHCH: Your new canvas is acrylic with indeed a thicker paper overlay.

ZHANG: This canvas seems abstract but I worked the shadows to make them stand out with charcoal. These are figurative art techniques.

LHCH: You seem to place a lot of importance on reflection.

ZHANG: A painting should not be done in reflection. But yes, in general, I reflect a lot on my artistic means.

LHCH: How do you define yourself between Europe and China?

ZHANG: Complex question! Because this year, I spent 19 years in China and I have been in Europe for 21 years! However, I never gave up my Chinese roots. I eat Chinese; I teach Chinese painting; my books are Chinese, etc. But indeed, there are things that I can only experience and learn here. Everyone builds identity in their own way, between different worlds at the same time.

LHCH: An example of what Europe has taught you.

ZHANG: Beauty doesn’t have to be especially beautiful. Also the idea that a painting can be “unfinished”.

LHCH: If I could try to summarize your journey so far, I would say that after working the real material of metal with engraving, then printed on Chinese paper and mounted; today, do you work the material directly on the paper using different inks, glues and papers?

ZHANG: The texture is figurative even if treated abstractly. I want to find the rule of a technique to give value to the unknown figurative, so to something that we cannot easily imagine! The figuration of a not already figured!

Pure abstraction does not exist. It always comes from an experience of nature, but enlarged or miniaturized until it becomes unknown.

LHCH: The arrival this year of a great contemporary Chinese painter at the Confucius Institute as part of a course on traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting is no coincidence…

ZHANG: Part of my course at La Cambre here in Brussels (I have been there since the start of the 2020 academic year with a growing number of students each year) is a month-long seminar on traditional Chinese landscape painting. I teach my students that landscape painting is the soul of a Chinese ink painting, which contains various elements such as poetry, philosophy, religion and nature. From imitating nature to following its deep tendencies, artists rely on hard work to develop observation and imagination. Another important relationship is the texture of the ink. I ask students to put aside their shyness and try adding salt, alkali, milk or any other material they think can be added to India ink, so that the effect of ink blur becomes more magical and unpredictable. When creating, in a practical sense, students can use their own artistic language to create images.

LHCH: A deep desire for transmission animates you

ZHANG: I thought a lot about how to introduce Chinese ink painting in European colleges. For me, ink painting is the essence of Chinese painting. Basic ink painting is only water and ink, it is black and white. The challenge is to transmit this art and to make students understand its importance, I would say universal. How to let European art students accept and master this foreign traditional painting technique is a huge challenge. But this year, Indian ink painting has gone from a temporary optional course at the National School of Visual Arts in La Cambre to a formal optional course. Dozens of students have mastered the basic method of Indian ink painting, and some of them may become the backbone of the Western art world in the future…